A value proposition consists of a combination of price, quality, and service, with consumers gravitating toward what they perceive as the best proposition. The speed at which the gravitation takes place depends on increases in the level of awareness combined with how compelling the value proposition is considered to be.

The level of awareness can be affected by several factors;

- The consumer's access to information (now virtually unlimited)

- The resources are available to promote and increase awareness of a value proposition.

- The motivation of a company to promote its new value proposition should it adversely affect an existing value proposition.

- How accessible the product is from within popular distribution channels that it may typically be purchased from.

As the awareness issues are resolved, they're followed by the rate of adoption that customers exhibit in taking up the value proposition.

Page-Wide Inkjet Printing Systems

We are interested in the page-wide inkjet array printing systems, how they are being deployed into the market, and future consumer repercussions. On the face of it, these systems are a great value proposition. The manufacturers (such as Hewlett Packard and Seiko Epson) are promoting their inkjet technology into business environments with a strong emphasis on far lower ownership costs (TCO) than laser-based printing platforms.

As detailed in our previous article, explaining why a transition from laser to inkjet-based systems will occur, inkjet has a poor track record in business environments where laser technology has historically been the overwhelming printing technology platform of choice. However, the enterprise versions of inkjet page-wide array systems are intended to change this with performance characteristics substantially better than those of comparable laser-based devices as well as a significantly lower cost of ownership. As more and more consumers become aware of the new value proposition, more and more will convert.

The Business Model

The business model (whether it's ink or laser) is no secret, with printers priced low enough to win market share but that generate little to no profit on the initial sale. The gains come later through selling replacement cartridges necessary for users to continue printing.

If the manufacturers were not confident of making profits on the future sale of replacement cartridges, they would have to raise the price of their printers to obtain a return on their investment. But, they don't want to do this because the consequence is to sell fewer machines, which means less demand for replacement cartridges. The prospect of fewer replacement cartridges introduces the problem of why there would have been a technology investment in the first place if there was to have been an insufficient return on investment to justify it.

Without cheap printers and expensive cartridges, perhaps we'd all still be using typewriters and dot-matrix printers.

The page-wide printhead array is an incredible piece of technology, having evolved over decades of incremental improvements from the original (now, by comparison, primitive) serial-technology-based inkjet systems. Today's product must have required the investment of many millions of dollars, perhaps hundreds of millions of dollars, to develop. Losing market share on replacement cartridges to third-party manufacturers places the acquisition of those dollars at risk.

The Market

To put the competition and respective market shares into perspective, over the 35 years or more of laser and inkjet systems, the aftermarket players operating in the United States have probably taken less than 20% market share. Furthermore, most of the aftermarket share is on monochrome printing devices (30%) and much less on color (10%), and the market share is predominantly in laser, not ink.

However, part of the reason the aftermarket is weak in the ink category is that the historical placement of inkjet has been in the small-office and home-office (SOHO) environment. When the major brick-and-mortar retailers carried aftermarket ink in the stores, the aftermarket had a more significant market share. Then, as the retailers faced more and more online competition and store foot traffic slowed, there ceased to be a justification for the shelf-space aftermarket alternatives required, so they were removed from distribution. Only a handful of companies selling aftermarket ink alternatives have the skills needed to sell online. As a result, overall aftermarket share in the inkjet category is probably significantly less today than fifteen years ago.

However, deploying the enterprise page-wide inkjet array systems will not be directed toward the SOHO channel. Instead, they will be directed toward businesses where the aftermarket has had more success competing with the original manufacturers. Therefore, because the aftermarket has a more substantial presence in the B2B distribution channels, it may open up an opportunity to win a more significant share of the replacement ink cartridge business.

Barriers to Entry

The barriers preventing aftermarket players from winning more outstanding market share are significant, with constant threats of litigation, channel-distribution issues, and ongoing marketing campaigns designed to spread fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD) about the risks of using aftermarket cartridges.

With these limitations in mind, what threats must the manufacturers of page-wide array inkjet systems, such as Hewlett Packard and Seiko Epson, contemplate as they promote these technology systems to the market?

- They are eroding their existing installed base of laser-based systems.

- Lower lifetime revenues generated by page-wide inkjet systems versus laser systems.

- The risks of losing replacement cartridge market share to third-party competitors.

For third-party competitors, there would appear to be a lower technology barrier to overcome to compete for market share with what amounts to little more than a plastic container of ink versus a complex, heavily patented laser toner cartridge. Because the technology barriers may be perceived to be lower, the manufacturers may also fear the potential for a more substantial loss of market share.

Regardless of the original manufacturer's massive investments in sophisticated, capital-intensive printers and printhead technology, the business model dictates the printers must be sold for little to no profit, and the annuity generated by the supplies must provide for the return on investment. Unfortunately for the manufacturers, the potential for profits on the replacement cartridges attracts competition, which has an advantage because it doesn't carry the burden of having to repay massive investments in printer and printhead technology.

Furthermore, although the printhead has been removed from the cartridge in these array systems, the cartridge now contains another element of technology that continues to serve as a barrier for would-be competitors. The new wall is a sophisticated, encoded computer chip placed on the cartridge to communicate with the printer, which may eventually become a more significant barrier to competition than the printhead ever was.

Business Practices

To illustrate the former point, let's consider the current practice of Seiko Epson. Epson does not guarantee its printers will perform if third-party replacement cartridges are installed. Although many purchasers of their printing devices may not readily understand or appreciate this when they make their purchase decisions, the terms are displayed on Epson's website and probably other locations, such as their point-of-sale packaging.

Seiko Epson has a practice of issuing regular firmware updates. Owners of their printers often see a message on the printer screen advising an update is available and prompting a decision to install it. Although no explanation is provided for why the update is necessary, most users will likely follow the onscreen prompts and install it anyway. By way of this process, it becomes possible for Epson to turn off third-party cartridges. After that, disgruntled owners who may have been using them may point to their website and show this possibility was covered under their original terms of sale.

This possibility becomes a massive deterrent for users of Epson printers ever to consider aftermarket replacement cartridge alternatives. It will likely be a significant factor in helping Epson protect replacement cartridge market share. The downside for Epson is that some savvy consumers may avoid their products and purchase a printer from an alternative manufacturer that doesn't have the same restriction.

It's possible Epson's practice could be serving to limit their printer market share development, but, on the flip side, the advantages accrued by retaining a very high market share on their profitable ink cartridges probably outweigh that disadvantage.

Hewlett Packard and the Class Action Lawsuit

Hewlett Packard doesn't currently place the same restriction on its sale of the PageWide series of inkjet printers (or any others to our knowledge), and consumers may now purchase their equipment with the expectation of having the option to buy less expensive third-party, non-HP replacement cartridges. Of course, common HP marketing materials discourage such actions and, understandably, heavily promote the continued use of HP-branded supplies.

However, in a chilling demonstration of what connectivity and the Internet of Things makes possible, on September 13, 2016, according to a complaint that ended up in the Northern District of California, thousands of HP printers in homes and offices around the country failed in unison. These failures resulted from HP implementing a firmware update that disabled printers containing ink cartridges manufactured by HP's competitors. The failed HP printers displayed an error message that the ink cartridges were damaged or missing and should be replaced. But the non-HP cartridges were neither damaged, lost, or out of ink.

Again, according to the complaint;

"HP devised and executed its firmware update as a means of gaining an advantage over its competition in the market for printer ink cartridges, which, over the life of the printer, typically cost more than the printer. HP did not announce its firmware update to consumers, and consumers did not anticipate it. With its update, HP acted by force to limit consumer choice and to take market share from its competition, instead of competing lawfully, based upon the quality and pricing of its ink cartridges."

On September 28, 2016, HP issued a veiled apology over a "dynamic security feature" in a firmware update that caused some HP inkjet models to display error messages and stop printing when using specific non-HP compatible inkjet cartridges using 3rd-party chips were installed.

The apology contained the following statement:

"We updated a cartridge authentication procedure in select models of HP office inkjet printers to ensure the best consumer experience and protect them from counterfeit and third-party ink cartridges that do not contain an original HP security chip and that infringe on our IP." [emphasis added]

To our knowledge, HP's intellectual property surrounding their so-called "security chip" has not been prosecuted, either to the point of a negotiated settlement that included an admission of infringement or to the end of a jury decision that correctly decided infringement. Until either event occurs, third-party cartridges containing non-HP chips cannot be determined to infringe on HP's intellectual property. Indeed, they cannot be determined by HP alone.

At best, it seems a self-serving determination that specific third-party replacement cartridges must infringe their intellectual property without the legal process determining this to be the case. This position appears to have been used by HP to justify to itself that it was okay to turn off printers remotely using third-party cartridges worldwide.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, HP's action led to the filing of numerous lawsuits in the United States, which were eventually consolidated into a single Class Action that, during the last eighteen months or so, has been winding its way through the legal process in the Northern District of California.

As one may expect, this process has been a lengthy and complicated one that we're not going to detail here, but on July 12, 2018, the plaintiffs and HP filed a joint notice of settlement, with Judge Davila signing the order the very next day. This order states, "The Parties have reached a settlement in principle to fully and finally resolve the litigation."

Details of the settlement are expected to be available sometime during September 2018, and, based on the "claims for relief" in the lawsuit, may be expected to include payment by HP for attorney's costs and court fees, an agreement not to commit similar actions in the future, and payment for damages to the Class.

Conclusions:

On the face of it, this pending conclusion to the legal action may appear to be a win for consumer rights and open up a potential threat to HP's future market share on its lucrative business for replacement ink cartridges used in their potentially "industry-changing" PageWide inkjet devices.

However, before consumers and third-party cartridge manufacturers start to celebrate, we need to compare the actions of HP with those of Seiko Epson.

HP "pushed" their firmware update onto printing devices they had originally manufactured but were now owned by their customers worldwide. Those customers did not provide their permission to install the firmware update and were oblivious to it taking place and to the consequences. This "push" and the absence of the owner's permission formed the basis of the complaints filed.

Seiko Epson's strategy is different. Firstly, they inform their customers that third-party consumables are not guaranteed to work on their printing devices. Secondly, they send a message to owners via the printer's control panel that an update is available to be installed. Even if the users are unaware of the reason for, or results of, that update, it's only performed as a result of an affirmative action by the user. Therefore, the update is not installed without the user's permission.

Depending on your own opinions, HP may or may not be considered to have acted in a manner befitting a blue-chip organization, proud of its technology and brand status in the marketplace when it decided to unilaterally update its firmware on certain inkjet printers without the owner's permission. That the lawsuits were filed meant specific individuals and their lawyers thought there were sufficient grounds to form the basis for a legal complaint alleging illegal conduct, and for which they were prepared to risk their time and capital to pursue a resolution.

Ultimately, HP probably decided to settle the Class Action because the risks associated with a jury trial and a potentially punitive monetary award against them were more significant than the outcome they believed they could achieve in a negotiated settlement.

Regardless of why they decided to settle, one of the outcomes may be a definition of the boundaries for what they may and may not do in the future if they continue to implement firmware updates that potentially turn off third-party replacement ink cartridges. These boundaries may be less demanding than those they risked facing if a court of law had imposed them.

Future Strategies and Consumer Acceptance of Restrictive Practices

One assumes HP currently prefers not to follow Epson's lead and tell potential customers in advance that they don't warranty third-party cartridges to work in their printers. Perhaps they'd like to avoid this because it may hinder their market share development objectives, particularly as they pursue their business goals in the so-called 50 billion dollars-a-year "A3" business vertical.

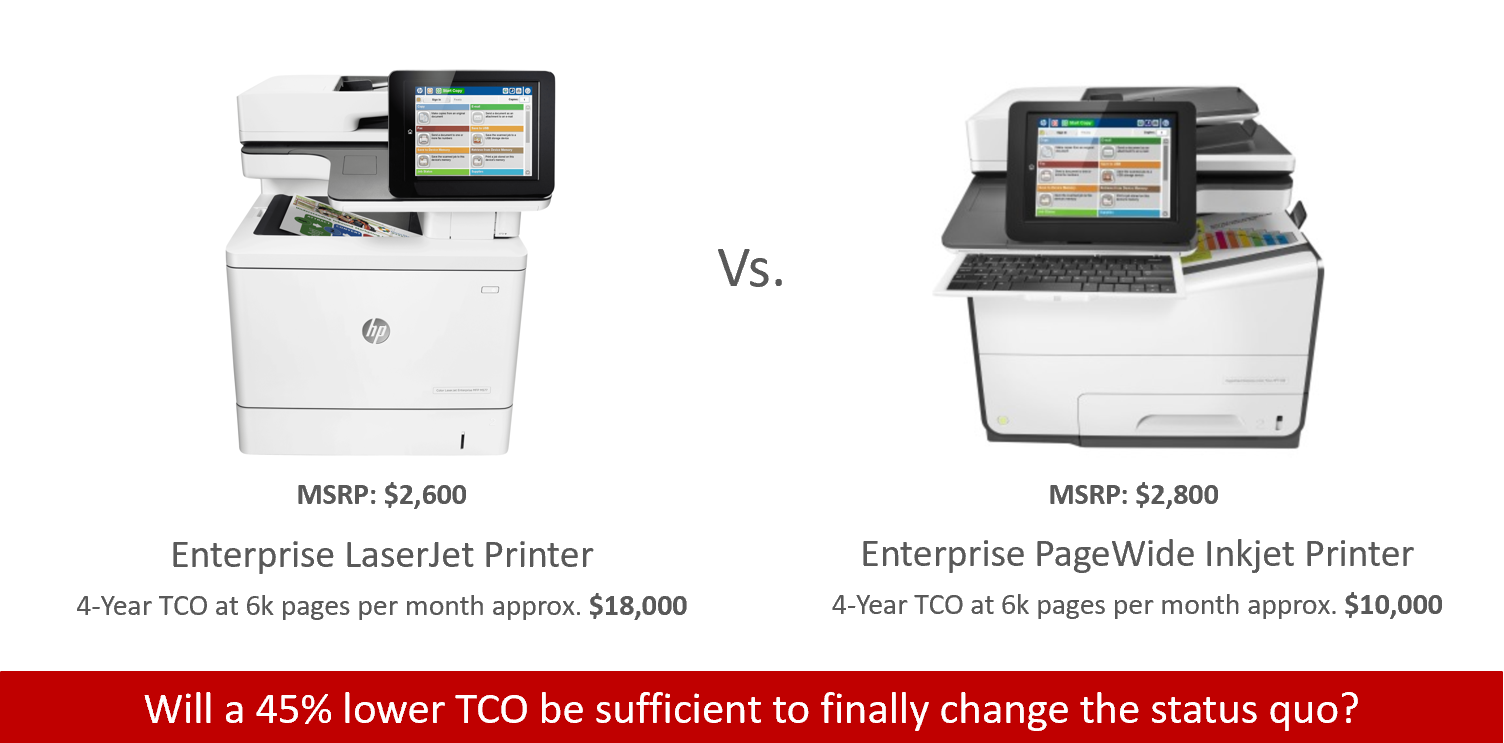

However, with a cost of ownership that can be as much as 50% lower than alternative laser-based systems, what if the value proposition that manufacturers of array-based inkjet systems now have become so compelling that other manufacturers lacking these capabilities are no longer able to compete?

One outcome of this scenario could be that the balance of power shifts sufficiently toward sellers of page-wide array inkjet systems (such as those offered by HP and Epson), allowing them to place more restrictive conditions on their sale openly. Indeed, it appears Epson has already decided it does because, as we've noted, they already published an upfront warning that third-party supplies cannot be guaranteed to work in certain circumstances, such as those that may occur during a user-installed firmware update.

Worse case, HP may adopt a similar strategy. The best chance, the terms of their negotiated settlement may permit them to adopt a softer approach while retaining enough flexibility to turn off third-party cartridges in some fashion.

It's not too difficult to believe customers may come to fully understand that, as they select a device that reduces their total cost of ownership by as much as 50%, one of the consequences may be having to accept third-party consumables that cannot be guaranteed to function. It's also not too difficult to believe that, with the prospect of a 50% reduction, they won't care and will willingly forsake the opportunity for 70%-plus reductions that may have been possible with third-party cartridge alternatives.

Zero TCO reduction, Vs. 50% TCO reduction, Vs. 70% TCO reduction?

Consumers will willingly forsake the opportunity for a 70% reduction in return for accepting certain restrictions necessary to get the 50% reduction because the alternative is a zero percent reduction!

In the face of such a compelling value proposition, most consumers would be unlikely to intensely object to a restriction involving third-party cartridges. Even if they harbored lingering doubts the manufacturer may increase the future price of replacement cartridges (knowing there would be no alternatives available for them to consider), the immediate opportunity to reduce TCO by 50% would likely be sufficient to overcome those doubts.

How significant a threat do page-wide array printing systems represent to the aftermarket?

The aftermarket may be facing one of the biggest challenges it has been confronted with. There are two components to this challenge.

- Aftermarket chip development is always behind the curve in reverse engineering its capability to match an OEM chip's functions. Behind the curve means it's always playing catch-up, and playing catch-up means reacting to developments already in the marketplace. A story in the market may be as simple as a firmware update that turns off old versions of aftermarket chips. Potential disruption of this nature will destroy the value proposition of the aftermarket products.

- While there may be too much competition in the laser-based printer market for individual manufacturers to successfully implement restrictions at the point of sale that turns off third-party printer cartridge alternatives, a more severe challenge faces the laser category.

We've often stated that new-build laser cartridges Vs. Remanufactured, that new-build must eventually win because a) they have a lower cost, and b) are (theoretically) higher quality. However, although these two factors combine to form a superior value proposition, this argument fails to contemplate the broader aspect of the overall market for office printing.

When using the same argument but applying it to Ink Vs. Laser, then ink wins because it has a lower cost than laser.

Page-array inkjet systems are genuinely disruptive to the office printing business.

- Over time, they can render laser printing obsolete, eliminating the demand for laser cartridges, whether OEM, remanufactured, or new-build.

- Point-of-sale restrictions permitting future actions that may compromise the reliable, uninterrupted performance of third-party inkjet cartridges could eliminate aftermarket ink alternatives from the market.

- Existing manufacturers of laser-based printing solutions that don't have access to wide-array inkjet systems risk being driven out of the office printing market.

While manufacturers lacking page-wide array inkjet systems may be able to compete in the short-term by lowering the price of their replacement cartridges sufficiently to reduce the TCO of their platforms to stay competitive with inkjet page-wide array systems, this action will result in such a hit to profitability, their ability (or desire) to invest in new products will be curtailed, and they will eventually be eliminated from the market.

For a final nail-in-the-coffin!

While the potential transformation of the printer fleet from laser-based technology to inkjet becomes a possibility, and while it carries with it the possible elimination of both remanufactured and new-build aftermarket toner cartridge alternatives, perhaps it spells an opportunity for remanufacturing used OEM inkjet cartridges.

It may be possible for the original OEM chips to be configured and reset to circumvent the crippling aspects of OEM firmware updates.

However, only one company (Clover Imaging Group) has the scale and infrastructure of the reverse logistics to recover sufficient quantities of used cartridges to make this business model viable, and, should such a possibility ever represent a threat, it would be possible (for HP by example) to eliminate the danger by way of an acquisition.

Such an event would neutralize the only remaining aftermarket player with deep distribution ties into the wholesalers and retailers in the United States and other global markets. If it ever transpired then, combined with a possible transformation of the printer fleet from laser to ink, as described in this article, HP would have been re-established as the overwhelmingly dominant player in the office printing space.